Group Exhibition: in this life(s)Feb 23 – Apr 6, 2024

In this life we will create and we will destroy; we will seek and search; we will dwell in the past and project into the future. In this life, we will question if there is another to come, and – no matter the answer – we will wonder, over and over, how best to spend what time we have.

Turning to Eastern philosophy, the artists Ash Roberts, Berend Boorsma and Mari-Ruth Oda are each influenced by the teachings of the Tao, the philosophy of Wabi Sabi and the practice of Kintsugi.

For the Dutch painter Berend Boorsma, Taoist philosophy and movement-based practices such as Tai Chi and Qi Gong offer a way into the work: “The main principle in Taoism is to act without acting, which doesn’t mean you don’t do anything – it means you only act when it comes from within. There is also the idea that things are in their natural state – that something is the way it is because that’s how it came into being. I try to find this feeling in my painting, as if the work was always there.”

Achieving this through color and texture, Boorsma creates a patina of sorts – a film, seemingly accrued over time, that covers the entire canvas, as if the process of aging has somehow been folded into its making. Sitting somewhere between abstraction and figuration, his compositions are untethered from place or context – and ultimately, one feels that he is simply in dialogue with the sun as it moves through the sky, waiting for the perfect conditions of light and shade that will bring his folded paper constructions to life.

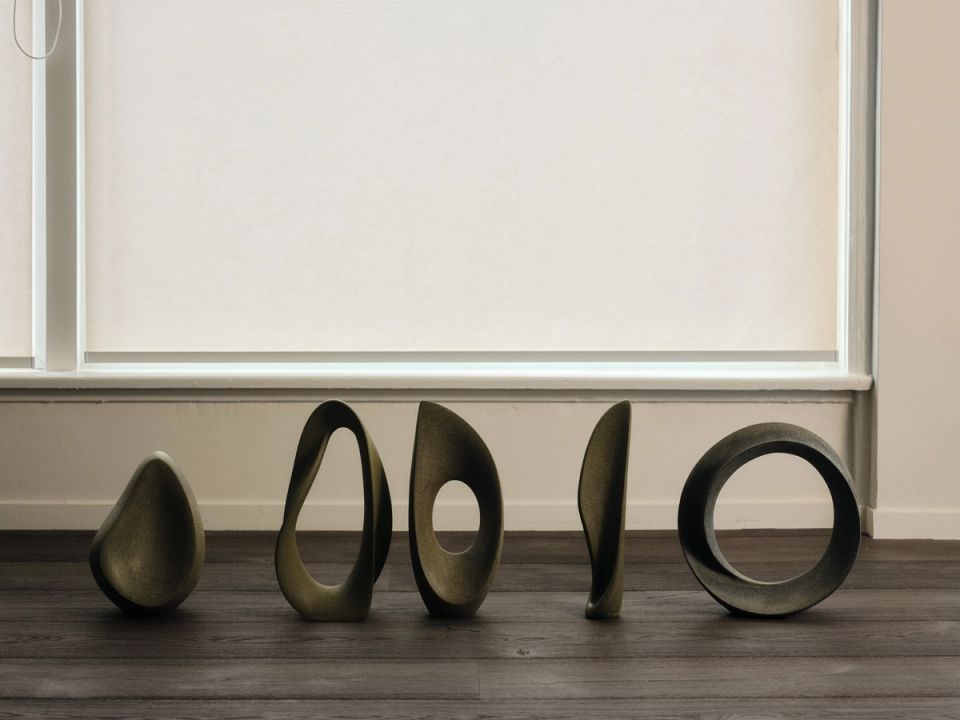

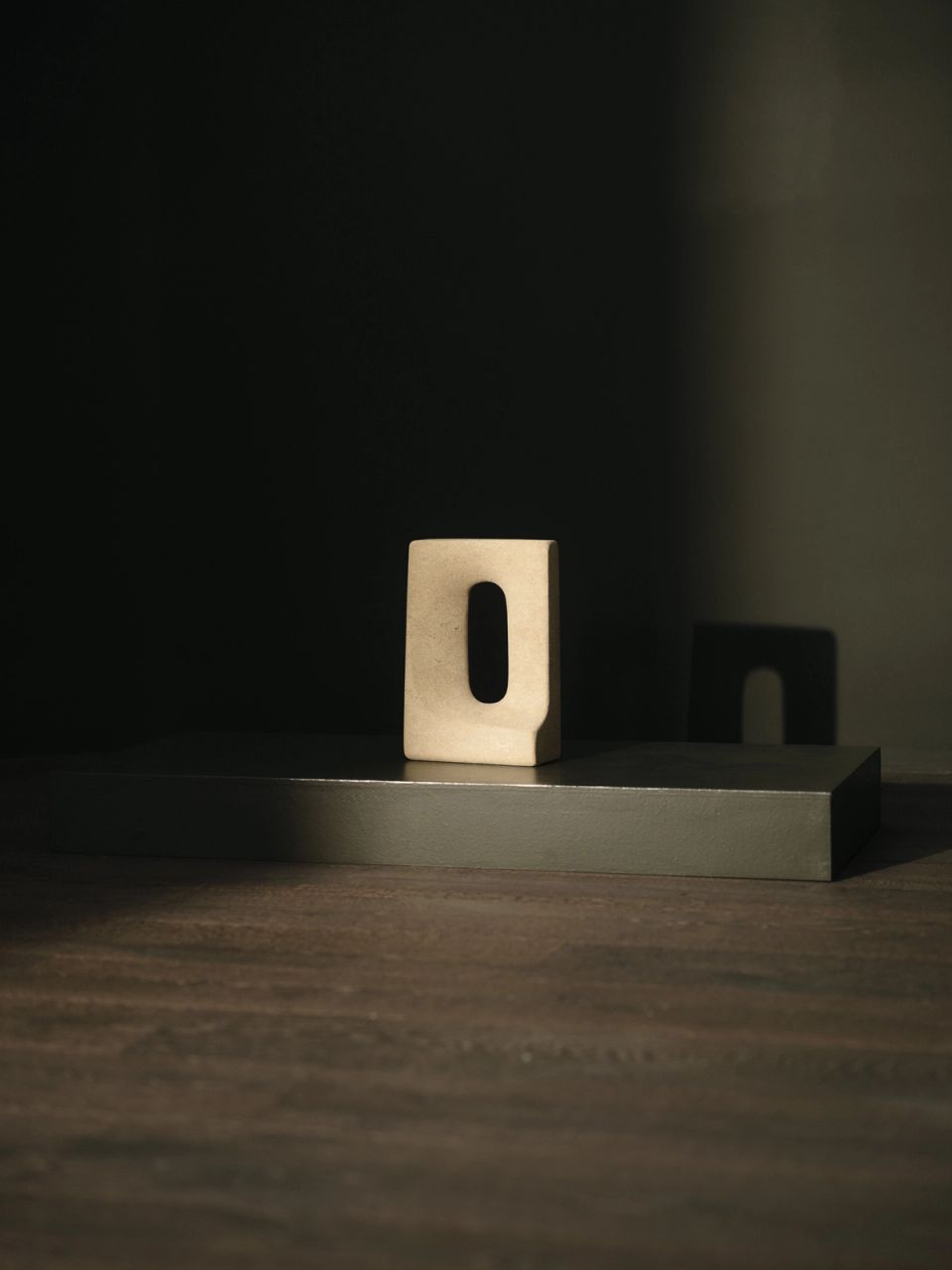

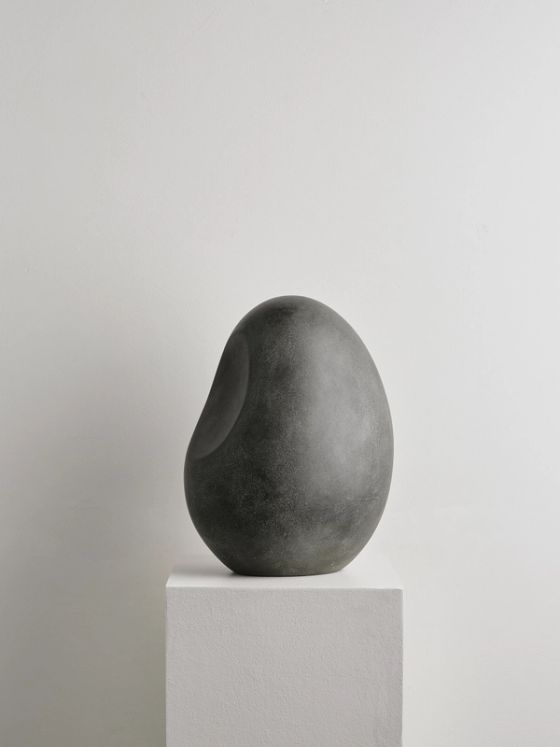

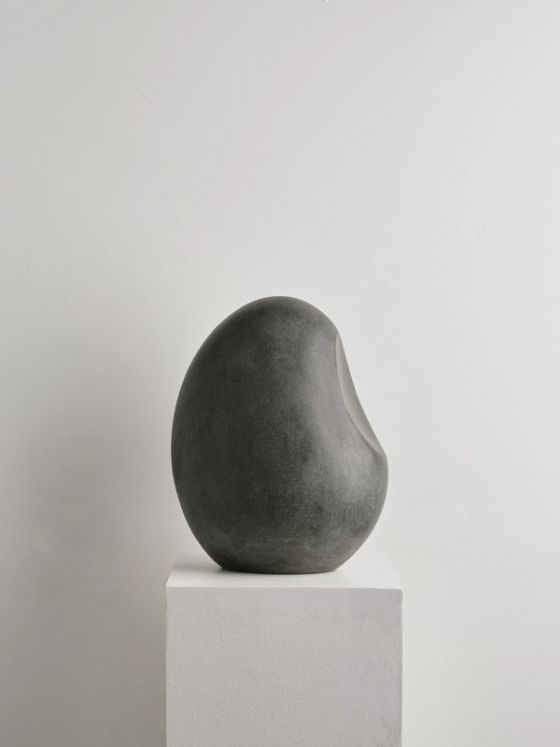

Ideas of creation and destruction, night and day, birth and death – the lifecycle of all things – are present amongst all three. For Roberts, it is the flowers that bloom to the surface in her painted ecosystems; for Oda it is in the looping Möbius strips, and the bean, seed and egg shapes that recur throughout her oeuvre.

Not so much about the natural world, as they are of it, Oda takes matter from the earth – the clay and stone beneath our feet – and transforms it into objects that refer back to their roots, to the land. Coal black, chalk white and “ancient green” finishes are achieved by kneading metals and minerals into the raw clay, so that color is baked into the object, rather than painted on afterwards as a glaze.

Whether thin and wispy or plump and rounded, it is as if each piece has been hollowed and hewn by water or wind, blasted into shape by the elements. In the studio, Oda’s practice does, in fact, seem to mimic the action and effect of erosion: whether built in clay or plaster, or carved from stone, the shapes and lines emerge through sanding, slowly removing one layer at a time. “It is through this process of sanding by hand that you become intimate with a work,” Oda notes. “That’s when it feels like the piece really comes to life.”

The land and landscape also act as muse for American painter Ash Roberts, whose canvases are misty and atmospheric, deep and serene, capturing the fleeting quality of our world. Her artistic enquiry has led her east, to Japan, where she has found a cultural kinship: a shared reverence for, and appreciation of, that which is ephemeral and ever-changing. In a nod to the philosophy of Wabi-Sabi and the practice of Kintsugi, Roberts employs gold leaf in her work – either patched across the entire surface or glimpsed in small flecks. Reacting to the room and changeability throughout the day, the gold sees her paint with light as well as color.

Ideas of time, and time passing, are inherent in all art, whether in the overt depictions of centuries past – the fanciful scenes of Heaven and Hell, or the gruesome Memento Mori, replete with rotting fruit, wilting flowers and undressed skulls – or in the more contemplative, abstracted spirituality that informs much of our contemporary, conceptual art.

There is an almost audible sense of quiet in the painterly compositions and sculptural forms of Boorsma, Oda and Roberts; a serenity that reaches near spiritual heights. From seemingly simple subject matter – a sheet of paper, a pebble, a pond – the artists tap into a collective visual language and transcend the specificity of any one person, culture or period.

Words

- Rosanna Robertson

Photos

- Rich Stapleton

Featured Works

LA Gallery

LA GalleryAsh RobertsAegean, 2024

LA Gallery

LA GalleryMari-Ruth OdaWitness, 2024

LA Gallery

LA GalleryMari-Ruth OdaA Narrow Passage, 2024

LA Gallery

LA GalleryBerend BoorsmaFramework I, 2017

Featured Artists

- Ash Roberts

The work of Helen Frankenthaler and the Color Field painters of the 1960s and 70s have been influential to Roberts, whose paintings feature large swaths of uninterrupted color – a melange of different tones which seem, suddenly, to crystallize into areas of figuration: a flower, leaf or lily pad appearing from the depths.

- Berend Boorsma

Each piece “starts with chaos, where anything can happen,” and slowly evolves over days and months, becoming more refined and distilled to its essence. Following Taoist principles, Boorsma tries “only to act when it comes from within. It is a process in which the painting finds its own form.”

- Mari-Ruth Oda

Oda’s serene, emotive sculptures reflect her fascination with fluid lines and natural forms, in materials such as jesmonite, resin and ceramics. “My work says more than I can with words.”

Related exhibitions

Form and Formless is Mari-Ruth Oda’s first solo show for Francis, featuring freestanding and wall-mounted sculptures in jesmonite and ceramic stoneware. Rounded natural forms are abundant in her work, appearing in the shapes of flowers, fruit, seeds, planets and moons. Many of her recent pieces have a quality of turning in on themselves, and exhibit a move towards symmetry. “At the start of 2020, I moved from Manchester to the tip of the Llŷn Peninsula in Wales,” says Oda. “The quiet has provided more headspace for me to work. I have been practising meditation too, which helps me to focus on the feeling in my body as I create. I’ve found that when I aim to convey this feeling, symmetrical forms arise, as if the sculptures are reflecting the natural symmetry of the human body.”

It is a hot, late September morning—quite typical of early autumn in California, but still tangibly at odds with the deepening quality of the light. I thread between lived-in Echo Park residences to climb the narrow stairs to John Zabawa’s studio, a small converted two-bedroom house that fits neatly within the domestic vernacular of the neighborhood. A pot is boiling on the stove of the kitchenette to make a cup of tea. Somehow, this detail, however slight, feels essential to the context—the paintings that rim the rooms are small domestic scenes: a flower arrangement, a plant, a portrait of a friend, a plate of lemons, a bottle of wine flanked by two half-filled glasses. Perched on a disused radiator, a platter holds nine lemons, unfussily arranged, their peels beginning to tarnish slightly the way peels do when left to the elements.