Ash Roberts & John Zabawa: Of MeritNov 2 – 10, 2024

It is a hot, late September morning—quite typical of early autumn in California, but still tangibly at odds with the deepening quality of the light. I thread between lived-in Echo Park residences to climb the narrow stairs to John Zabawa’s studio, a small converted two-bedroom house that fits neatly within the domestic vernacular of the neighborhood. A pot is boiling on the stove of the kitchenette to make a cup of tea. Somehow, this detail, however slight, feels essential to the context—the paintings that rim the rooms are small domestic scenes: a flower arrangement, a plant, a portrait of a friend, a plate of lemons, a bottle of wine flanked by two half-filled glasses. Perched on a disused radiator, a platter holds nine lemons, unfussily arranged, their peels beginning to tarnish slightly the way peels do when left to the elements.

Zabawa and I talk about how lemons are an irresistible archetype, a subject any viewer claims unconsciously without friction. Everyone has had an experience with a lemon, after all, and knows the sharp, astringent scent of its peel, the pucker of its tart flesh, the way a wedge flavors tea, a twist brightens a martini, the sweetened juice transforms into a ubiquitous refreshment. The accessibility of this image is what renders it at once universal and personal; Zabawa’s lemons are not specific lemons, but rather an idea of the fruit. They are a symbol of generosity and hospitality from his Korean background: the bowls of fruit arrayed in the home as asubliminal invitation. They are the lemons of Matisse, strewn across a tabletop; of Picasso, mingling with oysters; of William Scott, balanced like two naked egg yolks on a plate.

There is no denying that Zabawa’s still lives call to mind those of his forebears, the early 20th century pillars of modernist painting who introduced us to the Platonic—if not strictly veristic—versions of everyday objects: oranges in a bowl, eggs in a frying pan, a patterned tablecloth, a violin, a folded newspaper. Zabawa’s canvases deploy many of the aesthetic conventions pioneered by the great still life painters of the last century: flat areas of color, descriptive lines that etch hard contours, collapsed perspective, the distillation of objects encountered in daily life. He has a sure, deft hand when it comes to reducing a vase—or a face, for that matter—to its essence, and also to the selection of a palette: his rusts and ochres, nuanced blacks, slate blues, and pale greens vibrate confidently against terracottas and blushes. The sand-dollar shaped leaves of a eucalyptus branch shimmy in conversation with a mauve backdrop. A bowl beneath it contains a trio of ruddy pomegranates, their mythology lingering unspoken. Beside it, an unopened envelope lays belly up, expectant.

I think of the poet Robert Hass’s essay Images, in which he writes, “What we see clearly is not perhaps the heart of reality toward which the image leaps, but the quiet attention that is the form of the impulse to leap.” This line speaks elegantly to Zabawa’s process: the quiet attention, the sense of an image’s, or a moment’s, arrest. In this, poetry and painting share a genetics of intention. To distill a view, or an impression, in a manner that is at once economical and lyrical, is the imperative of both mediums. It is likely for this reason that looking at Zabawa’s work can feel a bit like reading a haiku:

A blank page awaits

lemons in a footed bowl

pot of ink still closed.

. . .

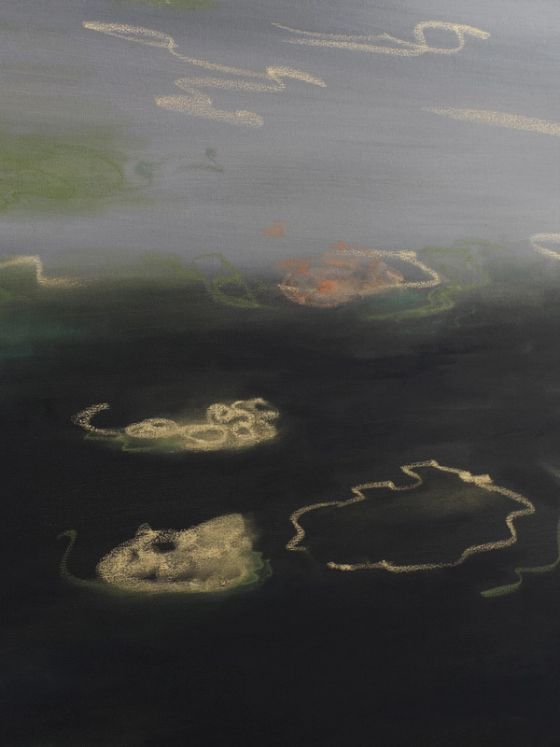

When I visit Ash Roberts, the light is strange. An overcast but warm day, without the swarm of light she is accustomed to having flood her Art Deco studio, a converted residence in Los Angeles’ Koreatown. The gold, she tells me, gesturing toward the work, would be aflame if the sun were out. In the refracted weather, there’s a pleasant dullness where luster might normally emerge—her canvases read to me as slightly melancholic. When she begins to explain the twin impetuses for this body of work, the tone clarifies: the death of a dear friend; a Robert Frost poem she encountered serendipitously shortly thereafter called Nothing Gold Can Stay. Several of the paintings she’s made bear titles derived from this poem:

“Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.”

This is the first time Roberts has folded gold into an entire collection. It’s a tricky medium to use; gold leaf electrifies gestures, renders passages incandescent. And yet, when the light doesn’t catch it, it can appear oxidized, washed-out, etiolated.

On Roberts’s studio walls, she has organized two distinct bodies of work: a series of thirteen small canvases (all measuring 22 x 27cm) and a quartet of larger tableaux, one of them a diptych. What unites them is the gold pigment and leaf used throughout, and the mood, which is equal parts wistful and mournful. I think of Cy Twombly’s series “Nini’s Paintings” from 1971, an homage to Nini Pirandello, the wife of Twombly’s gallerist Plinio De Martiis, who committed suicide that year. Twombly’s looping, repetitive gestures increasingly approach a state of writing, without crossing the threshold. Grief is an agonizingly liminal state, and Twombly's febrile layers of illegible writing and overwriting amount to letters to a friend he knew could never be read. Roberts’s mark-making veers into a Twombly-ish thicket in places, and I see her getting productively lost there. A place where the body takes over; the super-ego abdicates and the act of painting itself becomes a communion. The medium becomes a medium, a way to speak with the dead.

In her smaller canvases, Roberts engages far more directly with the subject at hand. In these, a cloud-like form iterates, sometimes lonely, sometimes hovering over the contours of a gilded landscape or a golden sky. A cloud is an apparition: a momentary coalescence of energy and water, a transmogrification, followed by a dissolution. Clouds, for this reason, are often ascribed a certain spiritual significance. They are in-between things, numinous symbols of the transitional space between one world and another. They are also timekeepers, mercurially marking the minutes, the seconds, as they change shape and vanish.

Roberts and I talk for a stretch about time, and how differently it is handled in the east and the west. Time, in Japanese culture, for instance, is not the vague and fleeting commodity that it is in America. Time is specific, the seasons measured in incremental, but tangible changes. There are rituals of reverence for the passage of time, whether manifest in literature or experienced at the dining table: for example, one eats ‘taranome,’ the bitter tree buds of the Japanese Angelica shrub, at the tail end of winter to savor the harshness of the season at the precise moment it begins to lift. There has been scientific research to substantiate the notion that deep observation of nature has the effect of elongating time, of expanding our sense of the world outside of ourselves, and of reestablishing equanimity. Whether Roberts’s clouds are real or imagined is incidental—they are the reifications of a closely studied interior landscape, an inward-looking that promises a kind of peace, untroubled by the weather.

Words

- Fanny Singer

Photos

- Billal Taright

Featured Works

LA Gallery

LA GalleryJohn ZabawaFernweh, 2024

LA Gallery

LA GalleryJohn ZabawaSelf Portrait, 2024

LA Gallery

LA GalleryJohn ZabawaBottle and Canvases, 2024

LA Gallery

LA GalleryJohn ZabawaL.A. Woman, 2024

Featured Artists

- Ash Roberts

The work of Helen Frankenthaler and the Color Field painters of the 1960s and 70s have been influential to Roberts, whose paintings feature large swaths of uninterrupted color – a melange of different tones which seem, suddenly, to crystallize into areas of figuration: a flower, leaf or lily pad appearing from the depths.

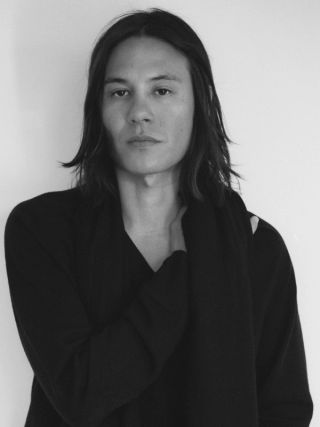

- John Zabawa

Spanning minimalist presentations and classical still lives, painter John Zabawa is not married to any school or style – instead, he seeks the best way to convey his message, to express something of himself and his process.

Related exhibitions

Though the phrase Bap meogeosseoyo? (밥먹었어요?) directly translates to “Have you eaten?”, it is a common greeting in Korean—a time-honored way of asking how someone is doing. Bap, meaning rice or a meal, frequently appears in Korean expressions, reflecting the cultural emphasis on nourishment as a foundation of being. The phrase is also deeply Korean in its politeness: its mundane and specific nature respects the boundaries of privacy while inviting a range of responses. Making use of this as a title, Have you eaten today? draws our attention to eating as one of the most fundamental acts of care, and an intimate form of relating to the world.

In this life we will create and we will destroy; we will seek and search; we will dwell in the past and project into the future. In this life, we will question if there is another to come, and – no matter the answer – we will wonder, over and over, how best to spend what time we have.

Illuminations can be both literal and metaphorical; one can illuminate with light or with knowledge. The latest body of work by the American painter, John Zabawa, developed out of this double meaning, their painted surfaces radiate outwards, their colours shimmering like the edges of the sun.

Bath Gallery

Bath GalleryJohn Zabawa: Gateways Apr 15 – Jun 19, 2021

Gateways is Los Angeles-based artist John Zabawa’s first solo show in the UK, featuring 24 oil paintings on canvas and wood. Their warm colours and abstract forms embody two branches of Zabawa’s art practice: a conceptual series of diptychs, and more figurative works, such as still life compositions of geometric fruit bowls and plants.