Group Exhibition: Have you eaten today?May 16 – Jun 12, 2025

Though the phrase Bap meogeosseoyo? (밥먹었어요?) directly translates to “Have you eaten?”, it is a common greeting in Korean—a time-honored way of asking how someone is doing. Bap, meaning rice or a meal, frequently appears in Korean expressions, reflecting the cultural emphasis on nourishment as a foundation of being. The phrase is also deeply Korean in its politeness: its mundane and specific nature respects the boundaries of privacy while inviting a range of responses. Making use of this as a title, Have you eaten today? draws our attention to eating as one of the most fundamental acts of care, and an intimate form of relating to the world.

Set in a 1929 Spanish colonial residence, the inaugural show at Casa Francis presents works by nine artists that meditate on the theme of sustenance. Painter John Zabawa’s canvas depicts rice, a staple in Korean cuisine, while Will Calver’s still lifes portray three kinds of nuts prevalent in California: walnut, almond, and pistachio. Their hard shells, whether cracked open or fully enclosed, nudge at our tactile desire to wedge open and consume—yet contained within each is a dormant possibility for new life. Calver’s canvases frequently illustrate plants and fruits that bloom, ripen, wilt, and decay: impermanent subjects guided by the temporal rhythms of life and death. These depictions of sustenance, in its most elemental form, not only render food as a form of nourishment, but as a medium through which the body and the land commune and cycles of life can be keenly experienced.

Elsewhere in the gallery, food is alluded to through its absence. A quiet sense of invitation permeates the gathering of what appears to be soft pebbles; Christina Kim of dosa has created cushions inspired by her childhood in Korea, particularly her memories of volcanic Jeju Island. The organic forms take their cue from five pebbles from the artist’s personal collection. Resourcefulness—a value shared between Kim’s oeuvre and Korean culinary culture—comes to the fore in the Pebble Series. With the help of Mumbai-based natural dyeing workshop Adiv, the artist made use of pulverized pomegranate peel and other botanical materials to create the subtle and unique patterns found on each cushion. During a visit to a Hindu temple, Kim learned of nirmalya, or “remnants" in Sanskrit. These sacred offerings of flower garlands and food, once ritually blessed, are handled with care even in their disposal— and some were used to leave their imprint on Kim’s fabric. The ongoing collaboration with Adiv renders the monoprint as an imprint of contact between the dye and the fabric, between the artist and her collaborators, and between cultures.

In a parallel gesture, the simplicity found in photographer Koo Bohnchang’s works emphasize the everyday, taking as its subject the humble spoon. The stillness in his photographs attunes us to the spoons’ patina, revealing itself through an accumulation of daily use, making the act of consumption as a continuation of tradition. The playful, subtle curves are not only an aesthetic decision, but a practical and carefully meditated space informed by generations of culinary heritage. Koo’s poetic portrait of spoons—from their origin in the Goryeo dynasty to contemporary times—brings our attention to the vast culture that guides our relationship with sustenance.

Echoing this sensibility, Nancy Kwon’s ceramics draw their formal inspiration from Korean ceremonial vessels. Kwon’s empty vessels embody her wishes for harmony and protection, symbolized by the celadon glaze and intentional choice of imagery. Similarly, Rahee Yoon’s lustrous acrylic vases—minimal and organic in form—recall the restrained beauty that is characteristic of Korean culture. Through meticulous sanding, Yoon reveals subtle expressions within the material while physically shaping space for water.

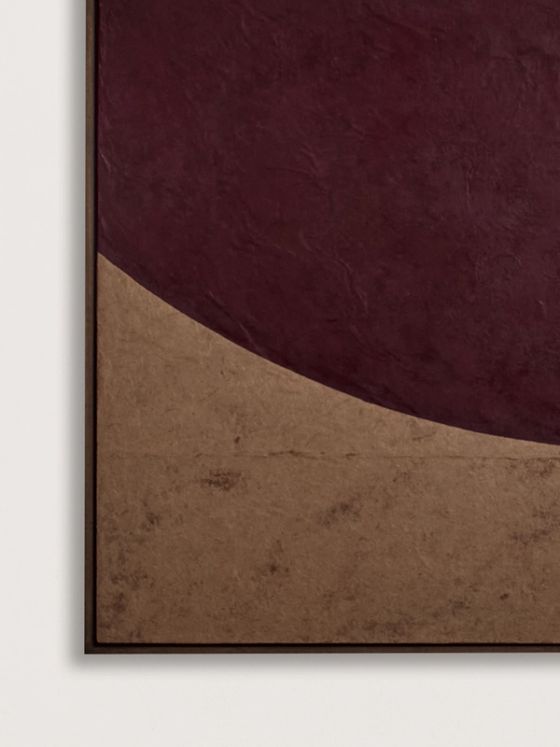

Further inside the exhibition space, the works of Ash Roberts and Yoona Hur inhabit each of the two bedrooms, offering a private space for contemplation. Every act of ingestion is followed by digestion, and here, art functions as a catalyst for the digestion of one’s lived experience. Roberts’s use of a folding screen, as well as imagery of curtains, creates privacy that facilitates a deeper connection to ourselves. In this new body of work, Roberts deploys silver paint and silver leaf to draw our attention to the ambiguity of appearances, and how “silver linings” can be found within, as the world around us shifts. In the adjoining room, Hur’s Inner Knowing series demonstrates the artist’s mature use of hanji, combined with circular forms and lines of pigment that expand beyond the canvas. The fragmentary compositions remind us that reality is always transmuting and partial. In Hur's paintings, trust permeates in place of the unknown, suggesting interconnectedness rather than separation. The work of both artists, placed in secluded parts of the home, highlights their source of sustenance as one that is derived from prolonged introspection, and asks us to look within.

Lindsey Chan, of Office of BC, created site-specific functional pieces for the show, which consider art in relation to the domestic. Her fireplace screen combines copper rods with shou sugi ban, a traditional Japanese technique for burning the surface of wood to offer durability and protection. The charred wood structure safeguarding the house from fire recalls the recent wildfires that affected surrounding communities in LA. The artist’s choice of shou sugi ban, therefore, can be read as a gesture of hope and resilience: an offering of care, both symbolic and literal, to the home and its inhabitants.

Each meal connects us to where we are from—whether geographic, cultural, or ontological—and reminds us that the daily act of eating is a willing participation in life and tradition. Making bap is an exercise of intuition and attention. From rinsing the rice to the final acts of consumption, nothing goes to waste. The water you rinse the rice with makes a base for a warm bowl of soup or stew. Every measurement relies on attentive, embodied intuition: you gauge the water by gently placing your fingers on the bed of rice, you listen to the soft percussion and notice the scent of each grain to know when it’s ready to come off the heat. Tteum, a brief moment of patience before uncovering the pot, is required for every good bowl of rice. This knowledge is passed down alongside a belief: that grains communicate with us. Our interaction with food deepens through learning its language and our commitment to listen. The land communicates to us through meals, asking us to notice all the ways in which we are cared for.

So when someone asks, “Have you eaten today?”—they are asking:

Are you taking care of yourself?

Are you paying attention to your everyday, to the changes in season, and to those around you?

Are you connected to the world that sustains you?

Words

- Min Park

Photos

- Rich Stapleton

Featured Works

LA Gallery

LA GalleryYoona HurInner Knowing 26, 2025

LA Gallery

LA GalleryKoo BohnchangSpoon 19, 2017

LA Gallery

LA GalleryAsh RobertsMujō, 2025

LA Gallery

LA GalleryRahee YoonHalf 2, 2025

LA Gallery

LA GalleryWill CalverPistachios, 2025

LA Gallery

LA GalleryAsh RobertsJacaranda, 2025

LA Gallery

LA GalleryRahee YoonHalf 1, 2025

LA Gallery

LA GalleryOffice of BC, Lindsey ChanHook, 2025

LA Gallery

LA GalleryYoona HurInner Knowing 24, 2025

LA Gallery

LA GalleryKoo BohnchangSpoon 01-1, 2017

LA Gallery

LA GalleryRahee YoonHalf 4, 2025

Featured Artists

- Ash Roberts

The work of Helen Frankenthaler and the Color Field painters of the 1960s and 70s have been influential to Roberts, whose paintings feature large swaths of uninterrupted color – a melange of different tones which seem, suddenly, to crystallize into areas of figuration: a flower, leaf or lily pad appearing from the depths.

- Christina Kim of dosa

Kim draws on traditional handwork techniques, particularly in India, Mexico, and Colombia, engaging local artisans and communities in long term collaborations.

- John Zabawa

Spanning minimalist presentations and classical still lives, painter John Zabawa is not married to any school or style – instead, he seeks the best way to convey his message, to express something of himself and his process.

- Koo Bohnchang

Koo Bohnchang dedicates much of his practice to capturing the passage of time. His celebrated series Vessels, taken over the course of 13 years, studies the frailty and beauty of Joseon-era baekja which Koo visited in major museums around the world.

- Office of BC, Lindsey Chan

OFFICE OF BC is a Los Angeles based multidisciplinary design firm led by Lindsey Chan and Jerome Byron, specializing in interior design and interior architecture for commercial and residential spaces.

- Nancy Jiseon Kwon

Nancy Jiseon Kwon creates ceramics, textiles and works in glass that are rooted in tradition and ritual. From ancient Korean stoneware and hemp burial gowns, to Etruscan votive offerings and Neolithic petroglyphs, her pieces are informed by a long tradition of ceremonial objects created from organic materials.

- Rahee Yoon

Yoon brings her experience in metalwork, textiles, ceramics, woodworking and resin-casting to create enigmatic objects that sit at the intersection of art and design. She studied arts and crafts at Sookmyung Women’s University in Seoul and opened her own studio in 2017.

- Will Calver

In studying the interactions between light, form and colour, British artist Will Calver’s still lifes convey the quietude and subtle monumentality of everyday objects.

- Yoona Hur

Yoona Hur is a ceramic artist based in Seoul and New York. Inspired by the full breadth of Korean ceramic history, from ancient earthenware to the white porcelain of the Joseon dynasty, her pieces both preserve and reinterpret this cultural heritage.

Related exhibitions

Illuminations can be both literal and metaphorical; one can illuminate with light or with knowledge. The latest body of work by the American painter, John Zabawa, developed out of this double meaning, their painted surfaces radiate outwards, their colours shimmering like the edges of the sun.

In Clear with Rising Mist, LA-based Nancy Jiseon Kwon explores the atmospheric, nostalgic and emotional potential of landscapes, particularly with reference to East Asian landscape painting and poetry from the 12th to 18th centuries, including the oeuvres of Song dynasty Chinese painter Xia Gui, Joseon dynasty Korean artist Jeong Seon, and Persian lyrical poet Hafiz. “I was thinking about the whole practice of landscape painting throughout East Asia – how travelling to beautiful landscapes created such an outpouring of creative expression that lasted centuries,” she says. “I’m intrigued by the idea of these artists observing the beauty of their surroundings and immortalising them through poetry and painting, in turn inspiring myths and nostalgic notions about the past. There was a movement towards unifying landscape, human form, and all elements of nature – I wanted to draw on this in my own pieces.”

It is a hot, late September morning—quite typical of early autumn in California, but still tangibly at odds with the deepening quality of the light. I thread between lived-in Echo Park residences to climb the narrow stairs to John Zabawa’s studio, a small converted two-bedroom house that fits neatly within the domestic vernacular of the neighborhood. A pot is boiling on the stove of the kitchenette to make a cup of tea. Somehow, this detail, however slight, feels essential to the context—the paintings that rim the rooms are small domestic scenes: a flower arrangement, a plant, a portrait of a friend, a plate of lemons, a bottle of wine flanked by two half-filled glasses. Perched on a disused radiator, a platter holds nine lemons, unfussily arranged, their peels beginning to tarnish slightly the way peels do when left to the elements.

Bath Gallery

Bath GalleryYoona Hur: LineageJul 1 – Aug 28, 2021

Lineage is Yoona Hur’s first solo show with Francis Gallery, featuring vessels inspired by traditional Korean forms, as well as organic ceramic sculpture, and canvas works in hanji, gesso, acrylic and glue. “There is multiplicity in the term lineage,” says Hur. “For me, it points to both traditional Korean art and craft, and the modern art movement Dansaekhwa – a distinct heritage that I deeply respect. The term also refers to nature and the environment, which is where the materiality and textural focus of my work stems from.”