Ben Nicholson: Tree, Column and Moon Feb 25 – Apr 9, 2021

Francis, in partnership with Larkhall Fine Art, is exhibiting 18 etching and drypoint prints by British artist Ben Nicholson (1894 - 1982). The prints were created during a short yet prolific period in the 1960s while Nicholson was living in Ticino, Switzerland. Writing in 1976, Nicholson described his fascination with etching:

Working on a copper plate is an extraordinary experience … the necessity of reducing my ideas to a system of lines interests me … My hand can at any point decide to make a curve, or other lines can join yet a larger curve or still another straight line even more rigid than one drawn with a ruler.

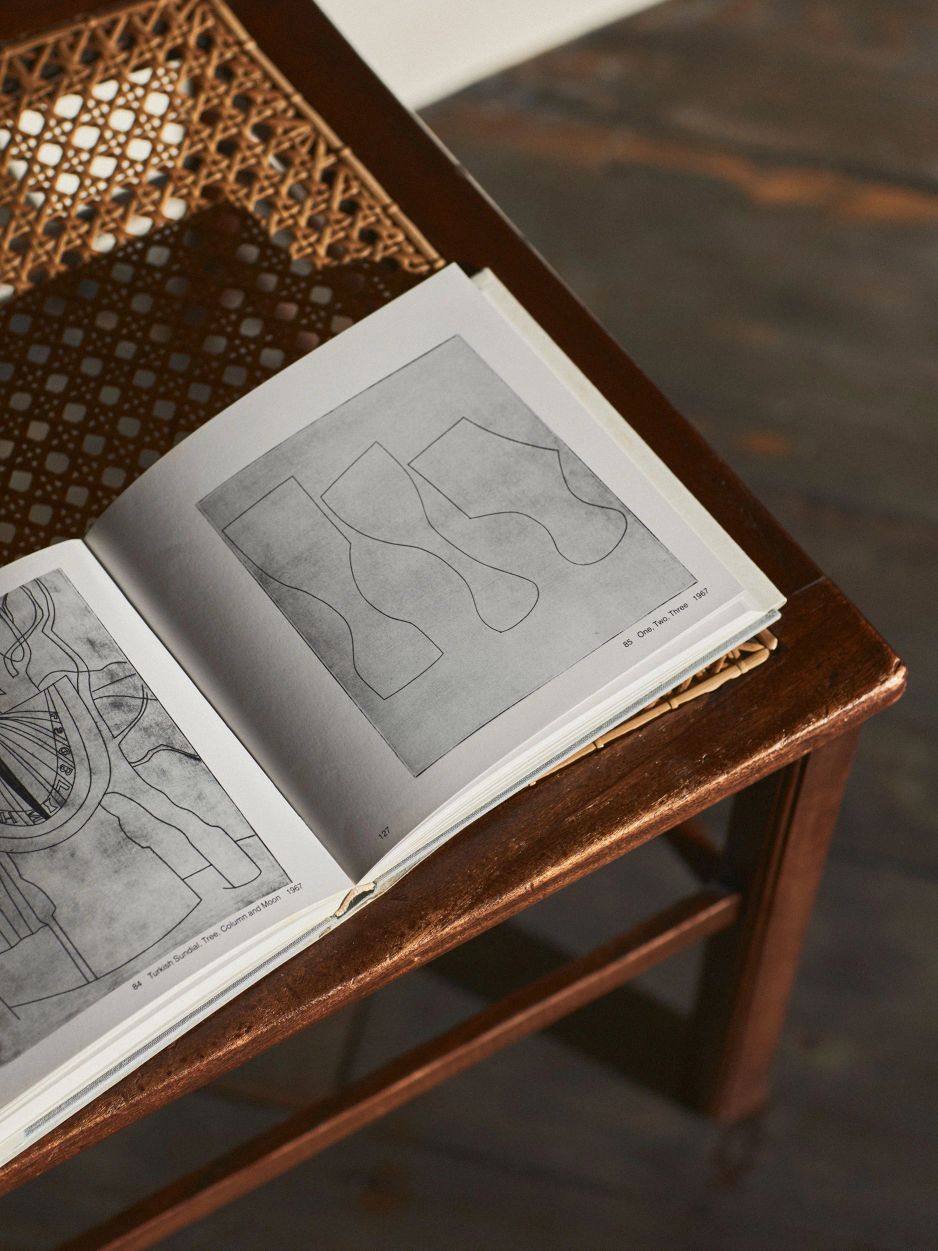

Etched into a primed copper plate that is then toned and printed, Nicholson’s gestures present a juxtaposition of curved and straight lines, producing abstract, geometric forms. Many take still lifes of goblets and bottles as their subject; elsewhere, column capitals, sundials, domes and cloisters meet the forms of trees and crescent moons, demonstrating Nicholson’s preoccupation with the landscapes and classical architecture of Italy, Greece and Turkey. Some compositions, such as Forms in a Landscape, are elegantly simple, balancing a series of sharp, essential strokes with minimal overlap. Others, such as Aegean, are more layered, and printed with a darker tone; here, smooth waves sweep across a multitude of forms, while a tight web scratches along the top of the composition, evoking the contrast of crashing waves with the tranquillity of the sea’s depths.

The prints were mostly published in editions of 50, while some in the show were created outside of these editions. Many come from the archive of François Lafranca, the Swiss printmaker who worked with Nicholson to produce his etchings. Writing in 1983, Lafranca reflected on his role as Nicholson’s printmaker:

The function of the pressman for the engraver can be likened to the function of the musician for the composer … he enters the universe of the artist and assists him in conveying his feeling, while adding something of his own.

Lafranca came to work with Nicholson after a chance encounter in an art shop in 1965. Lafranca was working as a painter, and had begun to dabble in etching and woodcuts. While he was purchasing printer’s ink, the storeowner asked Lafranca if he knew of a printmaker for a client of his. Lafranca, who was inexperienced at the time, ‘bluffed and claimed to be in a position to print such works,’ he wrote.

The pair produced all of Nicholson’s prints during this period, which involved over 120 etchings in four years. Nicholson used to visit Lafranca’s studio to decide on formats, and engrave the plates at his home, before returning to the studio to acidify the plates and begin printing. Many of the proofs that have survived have notes written by Nicholson, instructing Lafranca on how the plate should be toned, wiped and printed. ‘During this period I would go once or twice a week to Ben Nicholson’s house,’ wrote Lafranca. ‘At 75 he worked 11 hours a day and did not let himself be disturbed.’ The work continued until 1968, when Nicholson declared his etching phase to be over.

‘Nicholson was strict about the integrity of the print runs,’ wrote Lafranca. ‘After signing, the plates were scratched, partly by himself, partly by me.’ Two such cancelled copper plates feature in the show: one accompanying Storm Over Paros – an etching of sharp lines contrasting with a foreboding, heavy tone; and Palaestra with Moon – a proof also cancelled by Nicholson with a mark in blue ink, offering an intriguing palimpsestic image, and an insight into Nicholson’s working process.

Lauren Lott of Larkhall Fine Art, along with her late husband, Nicholas, has dealt in Nicholson’s etchings and drypoints since 1996. The pair tracked down François Lafranca and visited his home in Cerentino, Ticino, on several occasions over the years. “When Ben Nicholson left Switzerland in 1974, he left behind a huge body of work: etchings, drypoints, artist’s proofs and copper plates. Some time after, Lafranca was given the right to dispose of these items as he saw fit,” says Lott. “While the reliefs are purely abstract, there has always been a thread of Nicholson’s preoccupation with nature and geometry running through them: void and solid, circle and square, black and white. Nicholson’s favourite props – mugs, goblets, bottles, and teapots – reappear throughout his long career. The abstract reliefs are architectonic by nature, so it is understandable that a fascination with architecture, line, form, and order became a logical development in Nicholson’s oeuvre.”

Words

- Ollie Horne

Photos

- Rich Stapleton