Mikyung Kim: Sky, Wind and StarsFeb 10 – Apr 16, 2022

Korean artist Mikyung Kim’s geometric paintings are rooted in patience and thought. “My works are about my relationship with my surroundings, and the world,” she says. “They are records of my developing awareness of life and the perception of subtle feelings. Geometry is a vehicle that expresses the unfolding, overlaying, emptying, and connecting of my actions on the surfaces. The sense of touch, and the very act of painting, guides me toward the moment in which a painting is done. When the work is finished, it will reflect my way of being and my way of seeing.”

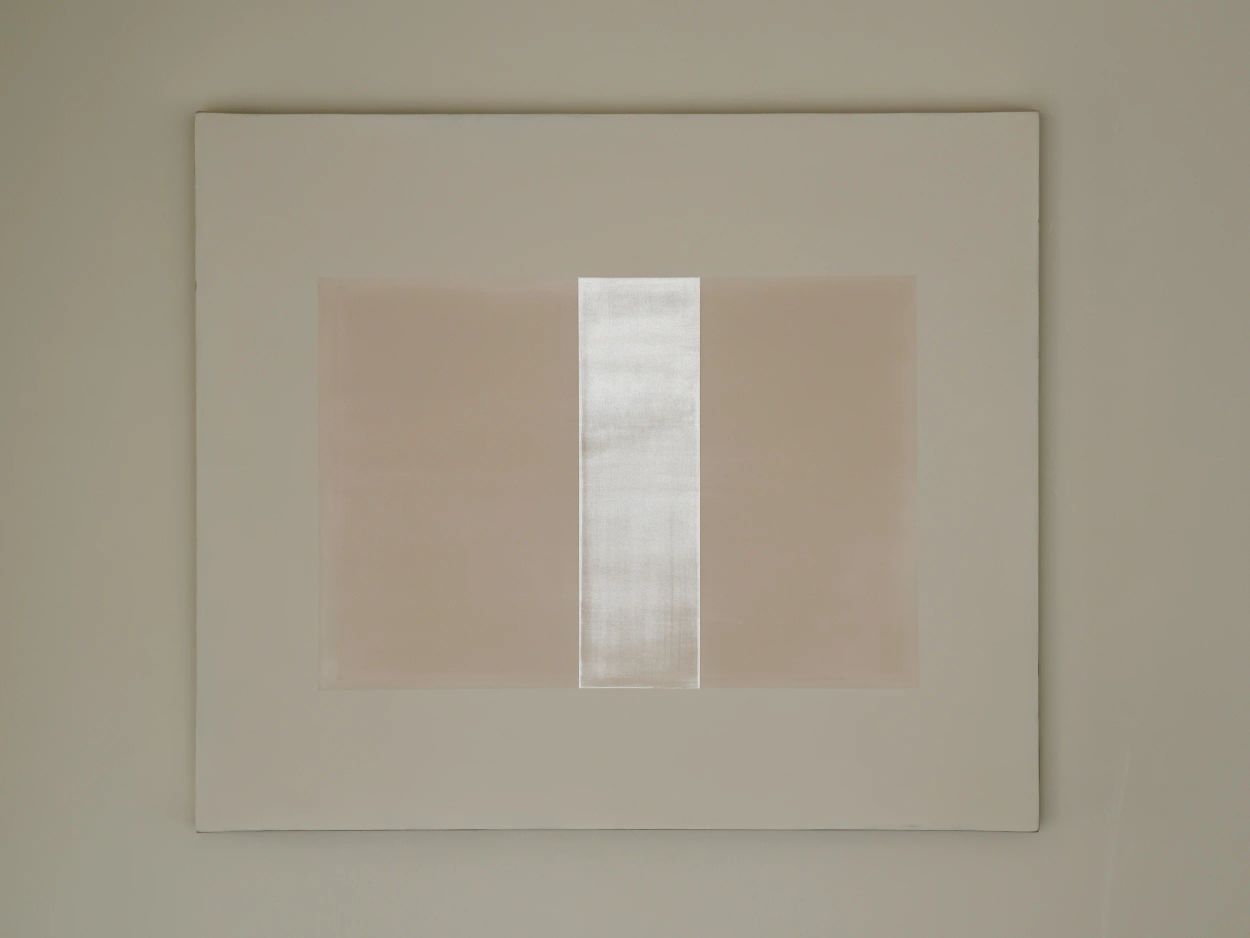

A series of six canvases, Yoondongju’s Sky, is intended to be viewed in one horizontal line. The rectangular paintings vary in size and orientation, and share a palette of gentle blues and pinkish creams and whites. Bands of colour suggest the horizon and the changing tones of the sky. The series references early 20th century poet Yun Dong-ju, whose poetry collection, Sky, Wind and Stars, lends its title to this show.

Kim’s paintings are deeply meaningful to her on a symbolic level, and much of her work concerns the figure of her mother. “One day, I realised that, up until that point, I had seen her as my mother only,” says Kim. “I began to think of her as a human being, and as a woman, too. My mother took care of her three children by herself for her whole life. I wanted to understand her existence, so I began writing out the numbers 1, 2 and 3, over and over again on a canvas.” This process is performed in Mountain I; at first glance, the green triangular form appears to be composed of calligraphic script, before a closer look reveals the numerals, their tightly packed arrangement vibrating against the ground.

This investigation of her mother’s life led Kim to consider the personal symbolism she found in bojagi – traditional Korean wrapping cloth. “My mother used a lot of bojagi for organising things at home, as we did not have much furniture,” she says. “When I was living in New York, I revisited Seoul, and found shops specialising in traditional bojagi. I was amazed at their beauty, and tried to imagine the state of mind of the makers when they were crafting them. They are so precious. Unfolded, they are flat, weightless, and take the form of a simple grid. But if we wrap things in them, the cloth adopts the shape of the objects within, without revealing the thing itself. I began using the grid shape of the unfolded bojagi in my works. Over time, this shape developed its own symbolic meaning. The grid form, to me, is like a cell of the mind, a piece of thought, a component of time. It prompts me to contemplate the origin of the mind, and by extension, the origin of human beings. I imagine the flat grid shape of my canvas is like an unfolded mind, which can collect other people’s minds, and in doing so, connect with them.”

Words

- Ollie Horne

Photos

- Genevieve Lutkin