Romy Northover: SanguineNov 23, 2021 – Jan 29, 2022

Undulating ceramic cups, waxed blocks of ebony, staffs of polished walnut, dramatic scrawls in charcoal, ethereal washes of black ink on paper. Romy Northover’s solo show, Sanguine, investigates a multitude of disciplines and materials, and meditates on questions of value, movement, performance, and the body in relation to its environment. “I spend a lot of time conceptualising and feeling into the work,” says Northover. “It’s almost like an athlete psyching themselves up for a race – a physiological preparation I need to go through before I can begin. We often talk about flow, but there is a lot of rigour that goes into my art making.”

Central to this preparation is Northover’s finely tuned connection with her environment. “The work for this show was composed during the pandemic, which brought with it a major change in environment: I moved to the Catskill Mountains in New York state; going from living in a city since I was 19 to being out in the country radically changed how I felt about my body and its position in the world,” says Northover.

This new environment manifests itself in her works in ink and paper, which were created by mixing India ink with fresh river water from the Catskills: “When I mixed the two together, something unexpected happened. It was like when you make tea with water from a different place: it tastes different. The ink suspended in the water in a unique way; with the minimum amount of touch, it began to move. I attained that state of pure being, free from thought, observing and allowing the ink and water to do what it wanted.”

This relinquishing of control can also be sensed in a series of ceramic cups, titled Once Again With Feeling, whose asymmetric forms appear to move as you observe them. Northover formed them on the wheel with her eyes shut, relying on intuition and muscle memory to guide her hands. “I hadn’t made any ceramics on a wheel for three years, and I was surprised by how much my body remembered,” she says. “Some of them broke, tore, or wiped out completely, but I tried to retain as much evidence of the process as possible. I’m interested in this question of where the consciousness lies in making: how present am I in the process, and when is the work being done? Is it in the action, or the time leading up to it, or after it? In another ceramic series in this show, called Stacked, I formed the cups while the wheel turned in the opposite direction. I like to see what results occur from these intentional disruptions. After many years making ceramics, I often consider what exactly we are looking for in terms of completion. Is it for each pot to look the same, without any interruptions? Or does perfection lie in how we feel when making the pot?”

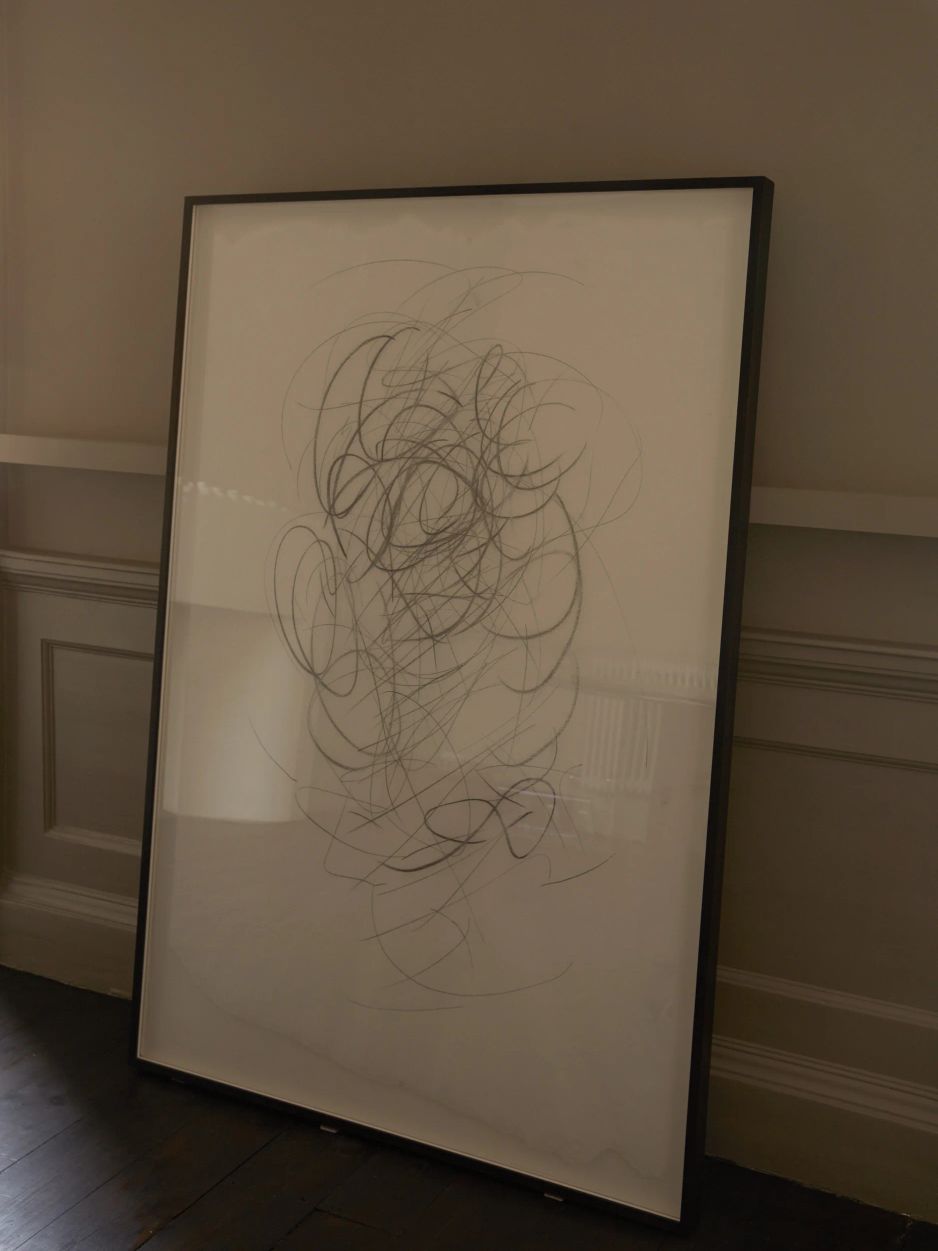

The series of charcoal drawings on paper followed a comparable method: eyes closed, inviting a performative composition governed by movement and feeling. The sheets of paper were rolled out and torn to match the full extension of Northover’s arms. Similarly, two sculptural staffs in the show were hand carved from walnut to match her wingspan, a way of connecting the work with her body, and investigating her positioning in the world. “One of the wood sculptures, titled Weight of the World, is intended to summon strength, and can be held across your shoulders or in your hand. It feels really empowering,” says Northover. “I think there are certain natural actions that can prompt your body to feel a certain way. When holding that staff, I suddenly felt I had more autonomy and power.”

Concepts of value are explored throughout the show with a juxtaposition of high and low materials, such as raw soil and polished walnut wood, or unglazed ceramics and burnished ebony blocks. In Intrinsic Value, raw terracotta soil is presented inside a silver box. “During the pandemic, I was fortunate enough to do an artist’s residency in Mallorca,” Northover explains. “I worked with terracotta that had been dug from the ground there. That direct connection with the clay was tremendous; it was so perfect in its raw state. It provoked me to consider the concept of value – why is clay one of those natural resources that people use and dispose of, while silver is considered more valuable? What is that system in which we conceive value? I hope these works honour how beautiful these natural materials are in their organic state. Water, soil – these things are precious, but are consistently undervalued in some societies. The elemental forces around us are powerful and valuable.”

Words

- Ollie Horne

Photos

- Sara Hibbert

Related exhibitions

Rounded, raw clay vessels on high plinths occupy the imposing ground floor windows of a Georgian townhouse. On another aspect, a solitary moon vase rests on a low pedestal, beside a shard of lichen-mottled bark: Francis Gallery is currently hosting its inaugural show, Modern Archive, at its new, permanent location at 3 Fountain Buildings, Bath. With a respectful attitude towards the Georgian site, gallery director Rosa Park and designer Fred Rigby has collaborated on an extensive renovation of the space. Ornamental cornicing and dados have been restored, and the floor has been stripped back to its original boards. Inspired by Korean aesthetics, with a nod to Bath’s quintessentially English heritage, the gallery’s collection is interspersed with both Korean and English antiques. Natural objects from the surrounding Somerset countryside – magnolia cones, piles of jade green moss, and sculptural bark – also accompany the artworks, providing further context.